Must we decolonise Open Access? Perspectives from Francophone Africa

A long read featuring the recent work of Thomas Hervé Mboa Nkoudou and Florence Piron, on how a truly open and inclusive ‘Open Access’ movement must include those at the periphery

I recently watched the recording of the fantastic Diversity, Equity and Inclusion session at OpenCon, and I was struck by the general theme of how ‘openness’ isn’t necessarily the force for equality that we perhaps think it is, and how issues of power, exploitation, and hierarchy means that it should be understood differently according to the context in which it is applied. In the session, Denisse Albornoz used the expression of ‘situated openness’ to describe how our Northern conception of openness should not be forced on anyone or any group – it needs to be understood first in individual contexts of historical injustices and post-colonial power structures.

What stood out for me most in this session, however, (because it related most to my work) was Cameroonian Thomas Mboa’s presentation, which talked about the ‘neo-colonial face of open access’. The presentation employed some very striking critical terms such as ‘cognitive injustice’ and ‘epistemic alienation’ to Open Access.

I’ve always known that the Open Access movement was far from perfect, but at least it’s moving global science publishing in the right direction, right? Can working towards free access and sharing of research really be ‘neo-colonial’ and lead to ‘alienation’ for users of research in the Global South? And if this really is the case, how can we ‘decolonise’ open access?

Thomas didn’t get much time to expand on some of the themes he presented, so I got in contact to see if he had covered these ideas elsewhere, and fortunately he has, through his participation in ‘Projet SOHA’ . This is a research-action project that’s been working on open science, empowerment and cognitive justice in French-speaking Africa and Haiti from 2015-17. He provided me with links to four publications written in French by himself and his colleagues from the project – Florence Piron (Université Laval, Quebec, Canada), Antonin Benoît Diouf (Senegal), and Marie Sophie Dibounje Madiba (Cameroon), and many others.

These articles are a goldmine of provocative ideas and perspectives on Open Access from the Global South, which should challenge all of us in the English-speaking academic publishing community. Therefore, I decided to share some excerpts and extended quotes from these articles below, in amongst some general comments from my (admittedly limited) experience of working with researchers in the Global South.

The quotes are taken from the following book and articles, which I recommend reading in full (these are easily translatable using the free tool Google Translate Web, which correctly translated around 95% of the text).

- Chapter 2 – ‘Les injustices cognitives en Afrique subsaharienne : réflexions sur les causes et les moyens de lutte’ – Thomas Hervé Mboa Nkoudou (2016), in Piron, Dibounje Madiba et Regulus 2016 (below)

- Justice cognitive, libre accès et savoirs locaux – Collective book edited by Florence Piron, Marie Sophie Dibounje Madiba and Samuel Regulus (2016) (CC-BY) https://scienceetbiencommun.pressbooks.pub/justicecognitive1/

- Qui sait ? Le libre accès en Afrique et en Haïti – Florence Piron (2017) (CC-BY) (Soon to be published in English in Forthcoming Open Divide. Critical Studies of Open Access (Herb & Schöpfel ed), Litwinbooks

- Le libre accès vu d’Afrique francophone subsaharienne – Florence Piron, Antonin Benoît Diouf, Marie Sophie Dibounje Madiba, Thomas Hervé Mboa Nkoudou, Zoé Aubierge Ouangré, Djossè Roméo Tessy, Hamissou Rhissa Achaffert, Anderson Pierre and Zakari Lire (2017) (CC-BY-NC-SA)

- Une autre science est possible. Récit d’une utopie concrète dans la Francophonie (le projet SOHA) – Revue Possibles, 2016 (CC-BY)

Piron et al’s (2017) article starts with a stinging critique of those of us in our Northern scholarly publishing community cliques, and our never-ending open access debates over technicalities:

“… there are many debates in this community, including on the place of open licenses in open access (is an article really in open access if it is not freely reusable in addition to being freely accessible?), on the legitimacy of the fees charged to authors by certain journals choosing open access, on the quality and evaluation of open access journals, on the very format of the journal as the main vehicle for the dissemination of scientific articles or on the type of documents to be included in institutional or thematic open archives (only peer-reviewed articles or any document related to scientific work?).

Viewed from Sub-Saharan Francophone Africa, these debates may seem very strange, if not incomprehensible. Above all, they appear very localized: they are debates of rich countries, of countries of the North, where basic questions such as the regular payment of a reasonable salary to academics, the existence of public funding for research, access to the web, electricity, well-stocked libraries and comfortable and safe workplaces have long been settled.” Piron et al. (2017)

… and their critique gets more and more scathing from here for the Open Access movement. OA advocates – tighten your seatbelts – you are not going to find this a comfortable ride.

“… a conception of open access that is limited to the legal and technical questions of the accessibility of science without thinking about the relationship between center and periphery can become a source of epistemic alienation and neocolonialism in the South”. Piron et al. (2017)

“Is open access the solution to the documented shortcomings of these African universities and, in doing so, a crucial means of getting scientific research off the ground? I would like to show that this is not the case, and to suggest that open access can instead become a neo-colonial tool by reinforcing the cognitive injustices that prevent African researchers from fully deploying their research capacities in the service of the community and sustainable local development of their country.” Piron (2017)

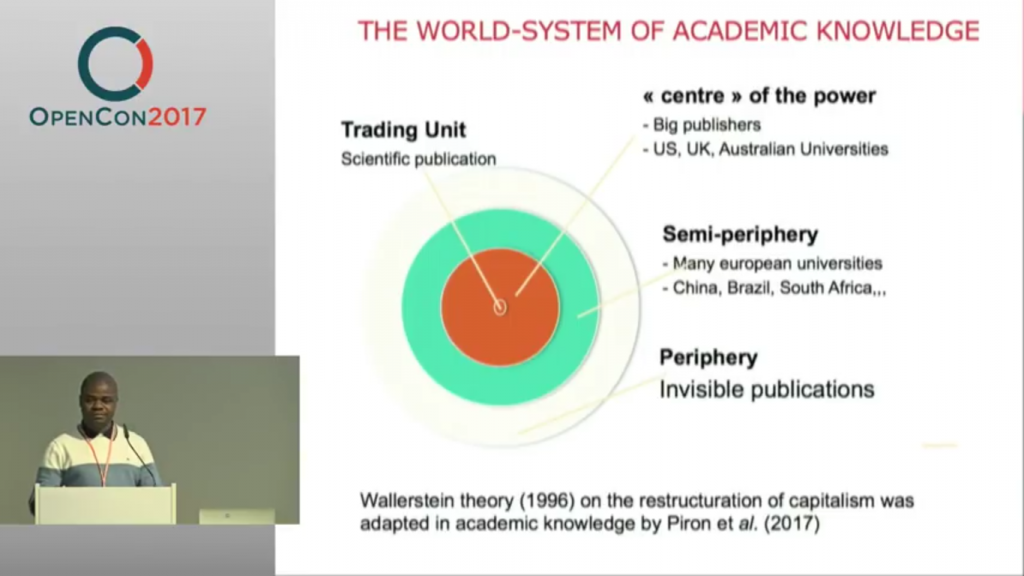

Ouch. To understand these concepts of ‘cognitive injustice’ and ‘epistemic alienation’, it helps to understand this ‘world system’ and the power relationship between the centre and the periphery. This is based on Wallerstein’s (1996) model, which Thomas featured in his OpenCon slides:

“… a world-system whose market unit is the scientific publication circulating between many instances of high economic value, including universities, research centers, science policies, journals and an oligopoly of for-profit scientific publishers (Larivière, Haustein, and Mongeon, 2015).” Piron et al. (2017)

“… we believe that science, far from being universal, has been historically globalized. Inspiring us, like Keim (2010) and a few others (Polanco, 1990), from Wallerstein’s (1996) theory, we consider that it constitutes a world-system whose market unit is the scientific publication. Produced mainly in the North, this merchandise obeys standards and practices that are defined by the ‘center’ of the system, namely the main commercial scientific publishers (Larivière, Haustein, & Mongeon, 2015), and their university partners are the US and British universities dominating the so-called world rankings. The semi-periphery is constituted by all the other countries of the North or emerging from the South which revolve around this center, adopting the English language in science and conforming to the model LMD (license, master, doctorate) imposed since the Bologna process to all the universities of the world with the aim of “normalizing” and standardizing the functioning of this world-system. The periphery then refers to all the countries that are excluded from this system, which produce no or very few scientific publications or whose research work is invisible, but to whom the LMD model has also been imposed (Charlier, Croché, & Ndoye 2009, Hountondji 2001)”. Piron et al. (2017)

So, the continuing bias and global focus towards the powerful ‘center’ of the world-system leads to the epistemic alienation of those on the periphery, manifesting in a ‘spiritual colonisation’:

“… this attitude that drives us to want to think about local problems with Western perspective is a colonial legacy to which many African citizens hang like a ball.” Mboa (2016).

So where does Open Access fit in with this world-system?

“… if open access is to facilitate and accelerate the access of scientists from the South to Northern science without looking into the visibility of knowledge of the South, it helps to redouble their alienation epistemic without contributing to their emancipation. Indeed, by making the work of the center of the world-system of science even more accessible, open access maximizes their impact on the periphery and reinforces their use as a theoretical reference or as a normative model, to the detriment of local epistemologies.” Piron et al. (2017)

Rethinking Northern perspectives

This should be an eye-opening analysis for those of us who assumed that access to research knowledge in the North could only be a good thing for the South. Perhaps we need to examine the arrogance behind our narrow worldview, and consider more deeply the power at the heart of such a one-way knowledge exchange. Many of us might find this difficult, as:

“The idea that open access may have the effects of neocolonialism is incomprehensible to people blind to epistemological diversity, who reduce the proclaimed universalism of Western science to the impoverished model of the standards imposed by the Web of Science model. For these people, the invisibility of a publication in their numerical reference space (located in the center of the world-system) is equivalent to its non-existence. The idea that valid and relevant knowledge can exist in another form and independently of the world-system that fascinates them is unthinkable.” Piron et al. (2017)

Having spent a little time at scholarly publishing events in the Global North, I can attest that the mindset described above is common. There are kind thoughts (and a few breadcrumbs thrown in the form of grants and fellowships) towards those on the periphery, but it is very much in the mindset of helping those from the Global South ‘catch up’. Our mindset is very much as Piron describes here:

“If one sticks to the positivist view that “science” is universal – even if its “essence” is symbolized by the American magazine Science – then indeed African science, that is to say in Africa, is late, and we need to help it develop so that it looks more and more like the North”. Piron (2017)

And whilst in the North we may have a lot of respect for different cultural perspectives, genuine reciprocal exchanges of research knowledge are rare. We are supremely confident that our highly-developed scientific publishing model deserves to be at the centre of our system. This can lead to selective blindness about the rigorousness of our science and our indexed journals, in spite of the steady drip drip drip of reports of biased peer review, data fraud and other ethical violations in ‘high-impact’ Northern journals, exposed in places like retraction watch.

North/South research collaborations are rarely equitable – southern partners often complain of being used as data-gatherers rather than intellectual equals and partners in research projects, even when the research is being carried out in their own country.

“These [Northern] partners inevitably guide the problems and the methodological and epistemological choices of African researchers towards the only model they know and value, the one born at the center of the world-system of science – without questioning whether this model is relevant to Africa and its challenges”. Piron et al (2017).

These issues of inequity in collaborative relationships and publication practices seem inextricably linked, which is not surprising when the ultimate end goal of research is publishing papers in Northern journals, rather than actually solving Southern development challenges.

“In this context, open access may appear as a neocolonial tool, as it facilitates access by Southern researchers to Northern science without ensuring reciprocity. In doing so, it redoubles the epistemic alienation of these researchers instead of contributing to the emancipation of the knowledge created in the universities of the South by releasing them from their extraversion. Indeed, by making the work produced in the center of the world-system even more accessible, free access maximizes their impact on the periphery and reinforces their use as a theoretical reference or as a normative model, to the detriment of local epistemologies, which generates situations absurd as, for example, the use of a theoretical framework related to wage labor in the Paris region to analyze the work of women in northern Mali” Piron (2017)

“The resulting consequences are, in particular, the teachers of the Southern countries who quote and read only writers from the North and impose them on their students and the libraries of our universities who do everything to subscribe to Western scholarly journals while they do not deal with our problems. (Mboa Nkoudou, 2016 )”

This is also a striking example:

“It is very sad to note that geographers in Ouagadougou are more familiar with European work on the Sahel than those at the Higher Institute of Sahel in Maroua, Cameroon.” Piron (2017)

The lack of equity in research knowledge exchange and collaboration is also caused by another one-way North to South flow: funding. Research in the South is often dependent on foreign funding. Big Northern donors and funders therefore set the standards and agendas in research, and in how the entire research funding system works. Southern partners rarely get to set the agenda, and researchers rarely get to develop the research questions that guide the research. They have to learn to jump through administrative hoops to become credible in the eyes of the Northern donor (for more information see ‘Who drives research in developing countries?‘).

Southern institutions are also compelled, via league tables such as the World Unviersity Rankings, to play the same game as institutions in the North. Institutions are ranked against each other according to criteria set in the North, one of which is citations (of course, only citations between journals in the Web of Science or Scopus, which is overwhelmingly Northern). And so to stay ‘competitive’, Southern institutions need their researchers to publish in Northern journals with Northern language and agendas.

Northern agendas and local innovation

Whilst it is tempting to think that the issues and criticism described above is mostly a problem for the social sciences and humanities, there are also real issues in the ‘hard’ sciences – perhaps not so much in their epistemological foundations – but in very practical issues of Northern research agendas. For example, Northern research, being based in Europe and the US, is overwhelmingly biased towards white people, in diversity of leadership, diversity of researchers, and most importantly in the whiteness of clinical trial subjects. This is problematic because different ethnic populations have different genetic makeups and differences due to geography, that mean they respond differently to treatments (see here, here and here). Are African and Asian researchers informed of this when they read research from so-called ‘international’ journals?

Furthermore, these Northern agendas can also mean that research focuses on drugs, equipment and treatments that are simply not suitable for developing country contexts. I was reminded of a discussion comment recently made by a Pakistani surgeon on the Northern bias of systematic reviews:

“There is a definite bias in this approach as almost all of the guidelines and systematic reviews are based on the research carried out in high income countries and the findings and the recommendations have little relevance to the patients, health care system and many a time serve no purpose to the millions of patients based in low resourced countries. e.g. I routinely used Phenol blocks for spasticity management for my patients which were abandoned two decades ago in the West. Results are great, and the patients can afford this Rs 200 phenol instead of Rs 15,000 Botox vial. But, unfortunately, I am unable to locate a single systematic review on the efficacy of phenol as all published research in the last decade was only on the use of Botox in the management of spasticity.” Farooq Rathore (HIFA mailing list, 2016).

Similarly, I’ve read research papers from the South that report on innovative approaches to medical treatments and other problems that utilise lower-cost equipment and methodologies (in fact, as is argued here, research in low-resource environments can often be more efficient and innovative, containing many lessons we, in the North, could learn from). This point is also made by Piron et al:

“… the production of technical and social innovations is rich in Sub-Saharan French-speaking Africa, as evidenced by the high number of articles on this subject in the Sci-Dev magazine, specializing in science for development, or in the ecofin site, an economic information agency turned towards Africa. But these are mostly local innovations that mobilize local resources and often recycled materials to, for example, introduce electricity into a village, better irrigate fields or offer lighting after sunset. The aim of these innovations is to contribute to local development and not to the development of international markets, unlike innovations designed in the North which, while targeting the countries of the South, remain highly marketable – just think of milk powder or GMO seeds. The issue of open access to scientific publications is a very secondary issue for local innovators in such a context”. (Piron et al. 2016)

These examples of innovation aside, there are many cases where the ‘epistemic alienation’ described above leads to ‘the exclusion or contempt of local knowledge’ (Mboa, 2016), even amongst researchers in the global South.

“In fact, Western culture abundantly relayed in the media and textbooks is shown to be superior to other cultures. This situation is pushing Africans to multiply their efforts to reach the ideal of life of the “white”. This situation seems to block their ability to think locally, or even to be reactive. Thus, faced with a given situation specific to the African context, many are those who first draw on the resources of Western thinking to propose elements of answers.” Mboa (2016)

Free and open access as ‘showcasing products’

The Research4Life (R4L) programme also comes in for criticism from Piron et al. which will come as a shock to Northern publishing people who often use the ‘… but they’ve got Research4Life’ line when faced with evidence of global research inequalities.

“… while pretending to charitably provide university libraries in the Global South with free access to pre-defined packages of paid journals from the North, this program, set up by for-profit scientific publishers, maintains the dependence of these libraries, limits their understanding of the true network of open access publications and, above all, improves the market for the products sold by these publishers.” Piron et al (2017)

“… this program encourages the continued reliance of these libraries on an external program, designed in the North and showcasing Northern products, while it may disappear as soon as this philanthropic desire is exhausted or as soon as trading partners will not find any more benefits.”

Whilst I still think R4L is a great initiative (I know many researchers in the Global South who are very appreciative of the programme), it’s difficult to disagree with the conclusion that:

‘… this program mainly improves the opportunities of Northern publishers without contributing to the sustainable empowerment of university libraries in the South … this charity seems very hypocritical, let alone arbitrary, since it can stop at any time.” Piron (2017)

Of course, the same could be said of Article Processing Charge (APC) waivers for developing country authors. Waivers are currently offered by the majority of journals from the big publishers (provided according to the same HINARI list of countries provided by Research4Life), although sometimes you have to dig deep into the terms and conditions pages to find them. Waivers are good for publishers to showcase their corporate social responsibility and provide diversity of authorship. However, they are unsustainable – this charity is unlikely to last forever, especially as they rely on the pool of Southern authors being relatively limited. It should also be noted that developing countries with the most active, growing researcher communities such as Nigeria, South Africa and India do not qualify for either R4L access or APC waivers.

Speaking of APCs, something I observe regularly amongst Southern researchers is a confusion over the ‘Gold’ OA author-pays model, and this too is noted:

“In northern countries, many researchers, especially in STEM (Björk and Solomon, 2012) [ 7 ], believe (wrongly) that open access now means “publication fees charged to authors” … this commercial innovation appears to be paying off, as these costs appear to be natural to researchers.” Piron (2017)

This also appears to be paying off in the Global South – authors seem resigned to pay some kind of charge to publish, and it is common to have to point out to authors that over two-thirds of OA journals and 99% of subscription journals do not charge to publish (although, the rise of ‘predatory’ journals may have magnified this misunderstanding that pay-to-publish is the norm).

It may be tempting to think of these inequalities as an unfortunate historical accident, and that our attempts to help the Global South ‘catch up’ are just a little clumsy and patronising. However, Piron argues that this is no mere accident, but the result of colonial exploitation that still resonates in existing power structures today:

“Open access is then easily seen as a means of catching up, at least filling gaps in libraries and often outdated teaching […] Africa is considered as lagging behind the modern world, which would explain its underdevelopment, to summarize this sadly hegemonic conception of north-south relations. By charity, Northern countries then feel obliged to help, which feeds the entire industry surrounding development aid [….] this model of delay, violently imposed by the West on the rest of the world through colonization, has been used to justify the economic and cognitive exploitation (Connell, 2014) of colonized continents without which modernity could not have prospered.” Piron (2017)

To build the path or take the path?

Of course, the authors do admit that access to Northern research has a role to play in the Global South, provided the access is situated in local contexts:

“… African science should be an African knowledge, rooted in African contexts, that uses African epistemologies to answer African questions, while also using other knowledge from all over the world, including Western ones, if they are relevant locally.” Piron (2017)

However, the practical reality of Open Access for Southern researchers is often overstated. There is a crucial distinction between making content ‘open’ and providing the means to access that content. As Piron et al. 2017 say:

“To put a publication in open access: is it, to build the path (technical or legal) that leads to it, or is it to make it possible for people to take this path? This distinction is crucial to understand the difference in meaning of open access between the center and the periphery of the world-system of science, although only an awareness of the conditions of scientific research in the Southern countries makes it possible to visualize it, to perceive it.”

This crucial difference between availability and accessibility has also been explained by Anne Powell on Scholarly Kitchen. There are many complex barriers to ‘free’ and ‘open’ content actually being accessed and used. The most obvious of these barriers is internet connectivity, but librarian training, language and digital literacy also feature significantly:

“Finding relevant open access articles on the web requires digital skills that, as we have seen, are rare among Haitian and African students for whom the web sometimes comes via Facebook … Remember that it is almost always when they arrive at university that these students first touch a computer. The catching up is fast, but many reflexes acquired since the primary school in the countries of the North must be developed before even being able to imagine that there are open access scientific texts on the web to make up for the lack of documents in the libraries. In the words of the Haitian student Anderson Pierre, “a large part of the students do not know the existence of these resources or do not have the digital skills to access and exploit them in order to advance their research project”. Piron (2017)

Barriers to local knowledge exchange

Unfortunately, this is made even more difficult by resistance and misunderstanding of the internet and digital tools from senior leadership in Africa:

“Social representations of the web, science and copyright also come into play, especially among older academics, a phenomenon that undermines the appropriation of digital technologies at the basis of open access in universities.” Piron et al. (2017)

“To this idea that knowledge resides only in printed books is added a representation of the web which also has an impact on the local resistance to open access: our fieldwork has allowed us to understand that, for many African senior academics, the web is incompatible with science because it contains only documents or sites that are of low quality, frivolous or entertaining. These people infer that science in open access on the web is of lower quality than printed science and are very surprised when they learn that most of the journals of the world-system of science exist only in dematerialized format. … Unfortunately, these resistances slow down the digitization and the web dissemination of African scientific works, perpetuating these absurd situations where the researchers of the same field in neighboring universities do not know what each other is doing”. Piron et al. (2017)

This complaint about in-country communication from researchers in the South can be common, but there are signs that open access can make a difference – as an example, in Sri Lanka, I’ve spoken to researchers who say that communicating research findings within the country has always been a problem, but the online portal Sri Lanka Journals Online (currently 77 open access Sri Lankan journals) has started to improve this situation. This project was many years in the making, and has involved training journal editors and librarians in loading online content and improving editorial practices for open access. The same, of course, could be said for African Journals Online, which has potential to facilitate sharing on a larger scale.

Arguably, some forms of institutional resistance to openness in the Global South have a neocolonial influence – universities have largely borrowed and even intensified the Northern ‘publish or perish’ mantra which focuses the academic rewards system almost entirely on journal publications, often in northern-indexed journals, rather than on impact on real world development.

“The system of higher education and research in force in many African countries remains a remnant of colonization, perpetuated by the reproduction, year after year, of the same ideals and principles. This reproduction is assured not by the old colonizers but by our own political leaders who are perpetuating a system structured according to a classical partitioning that slows down any possible communication between researchers within the country or with the outside world, even worse between the university and the immediate environment. For the ruling class, the changes taking place in the world and the society’s needs seem to have no direct link to the university.” Mboa (2016)

Mboa calls this partitioning between researchers and outsiders as “a tight border between society and science”:

“African researchers are so attached to the ideal of neutrality of science and concern of its ‘purity’ that they consider contacts with ordinary citizens as ‘risks’ or threats and that they prefer to evolve in their ‘ivory tower’. On the other hand, ordinary citizens feel so diminished compared to researchers that to talk to them about their eventual involvement in research is a taboo subject …” Mboa (2016)

Uncolonising openness

So what is the answer to all these problems? Is it in building the skills of researchers and institutions or a complete change of philosophy?

“The colonial origin of African science (Mvé-Ondo, 2005) is certainly no stranger to this present subjugation of African science to northern research projects, nor to its tendency to imitate Western science without effort. Contextualization, particularly in the quasi-colonial structuring of sub-Saharan African universities (Fredua-Kwarteng, 2015) and in maintaining the use of a colonial language in university education. Considering this institutionalized epistemic alienation as yet another cognitive injustice, Mvé-Ondo wonders “how to move from a westernization of science to a truly shared science” (p.49) and calls for “epistemological mutation”, “rebirth”, modernizing “African science at the crossroads of local knowledge and northern science – perhaps echoing the call of Fanon (1962/2002) for a “new thinking” in the Third World countries, detached from European model, decolonized.” Piron et al. (2017)

For this to happen, open access must be about more than just access – but something much more holistic and equitable:

“Can decentralized, decolonised open access then contribute to creating more cognitive justice in global scientific production? Our answer is clear: yes, provided that it is not limited to the question of access for scientific and non-scientific readers to scientific publications. It must include the concern for origin, creation, local publishing and the desire to ensure equity between the accessibility of the publications of the center of the world system and that of knowledge from the periphery. It thus proposes to replace the normative universalism of globalized science with an inclusive universalism, open to the ecology of knowledges and capable of building an authentic knowledge commons (Gruson-Daniel, 2015; Le Crosnier, 2015), hospitable for the knowledge of the North and the South”. Piron et al. (2017)

Mboa sees the solution to this multifaceted problem in ‘open science’:

“[Cognitive injustice comes via] … endogenous causes (citizens and African leaders) and by exogenous causes (capitalism, colonization, the West). The knowledge of these causes allowed me to propose ways to prevent our downfall. Among these means, I convened open science as a tool available to our leaders and citizens for advancing cognitive justice. For although the causes are endogenous and exogenous, I believe that a wound heals from the inside outwards.” Mboa (2016).

Mboa explains how open science approaches can overcome some of these problems in this book chapter, but here he provides a short summary of the advantages of open science for African research:

“It’s a science that rejects the ivory tower and the separation between scientists and the rest of the population of the country. In short, it’s a science released from control by a universal capitalist standard, by hierarchical authority and by pre-established scientific classes. From this perspective, open science offers the following advantages:

- it brings science closer to society;

- it promotes fair and sustainable development;

- it allows the expression of minority and / or marginalized groups, as well as their knowledge;

- it promotes original, local and useful research in the country;

- it facilitates access to a variety of scientific and technical information;

- it is abundant, recent and up to date;

- it develops digital skills;

- it facilitates collaborative work;

- it gives a better visibility to research work.

By aiming to benefit from these advantages, researchers and African students fight cognitive injustice. For this, open access science relies on open access, free licenses, free computing, and citizen science.” Mboa (2016).

But in order for open science to succeed, digital literacy must be rapidly improved to empower students and researchers in the South:

“Promoting inclusive access therefore requires engaging at the same time in a decolonial critique of the relationship between the center and the periphery and urging universities in the South to develop the digital literacy of their student or teacher members.” Piron et al. (2017)

It also requires improving production of scientific works (‘grey’ literature, as well as peer-reviewed papers) in the South for a two-way North/South conversation:

“Then, we propose to rethink the usual definition of open access to add the mandate to enhance the visibility of scientific work produced in universities in the South and thus contribute to greater cognitive justice in global scientific production.” Piron (2017)

And providing open access needs to be understood in context:

“… if we integrate the concern for the enhancement of the knowledge produced in the periphery and the awareness of all that hinders the creation of this knowledge, then open access can become a tool of cognitive justice at the service of the construction of an inclusive universalism peculiar to a just open science.” Piron, Diouf, Madiba (2017)

In summary then, we need to rethink the way that the global North seeks to support the South – a realignment of this relationship from mere access to empowerment through sustainable capacity building:

“Africa’s scientific development aid, if it is needed, should therefore be oriented much less towards immediate access to Northern publications and more to local development of tools and the strengthening of the digital skills of academics and librarians. These tools and skills would enable them not only to take advantage of open access databases, but also to digitize and put open access local scientific works in open archives, journals or research centers.” Piron (2017)

So what next?

Even if you disagree with many the above ideas, I hope that this has provided many of you with some food for thought. Open Access must surely be about more than just knowledge flow from North to South (or, for that matter the academy to the public, or well-funded researchers to poorly funded researchers). Those on the periphery must also be given a significant voice and a place at the table. For this to happen, many researchers (and their equivalents outside academia) need training and support in digital skills; some institutional barriers also need to be removed or overcome; and of course a few cherished, long-held ideas must be seriously challenged.

“These injustices denote anything that diminishes the capacity of academics in these countries to deploy the full potential of their intellectual talents, their knowledge and their capacity for scientific research to serve their country’s sustainable local development”. Piron et al., (2016).

What do you think…?

————————————————————————————————————

Thanks to Florence and Thomas for double-checking the translations of their work from the French originals.

The rest of the material above represents my own personal thoughts, and does not necessarily represent the views of my employer.

This article is licensed under the terms of a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-SA